Southeast Asia is a paradox. By any account it should be a major contributor to the global food supply, not only producing enough for itself for the rest of the world as well. This is a region which contributed 7 percent of the global food market in 2022, and where agriculture accounts for more than 11 percent of total regional GDP. Yet, as of 2023, the region’s population were still undernourished with 26.4 percent of children under the age of five suffering from stunted growth due to poor nutrition according to the UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group Joint Malnutrition Estimates 2023 Report, despite the optimistic downward trend from the high of 30.4 percent in 2012.

Even with this brighter outlook, one must still ponder on the question of how is it that a region, which is a major producer of commodities such as rice, palm oil, tropical fruits, vegetables and seafood – to name a few – is still unable to adequately feed itself? What are the main issues to this problem? What needs to be done to help it realise its potential to be the food basket of the world?

Regional Agriculture and Food Security Metrices

Presently, the combined population of Southeast Asia – which comprises Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Timor-Leste – is estimated to be more than 660 million. This is expected to increase to more than 720 million by the year 2030.

Of the 11 countries in Southeast Asia, Cambodia is the country where agriculture has the highest contribution to the country’s GDP, with Singapore being the lowest. Agriculture makes up more than 10 percent of the GDP in five countries, with Brunei and Singapore being the only two countries where the sector accounts for less than 5 percent of GDP.

The ASEAN Statistical Year Book 2022 reports that agriculture also contributed to 31.9 percent of employment in Thailand in 2021, 29.1 percent in Vietnam, 28.3 percent in Indonesia, 24.2 percent in the Philippines, and 10.3 percent in Malaysia. While the data for the remaining countries are not available, it would not be wrong to surmise that agriculture is responsible for a significant percentage of employment there, given the share the sector has in their GDPs.

Also, of the 10 ASEAN countries, only Singapore is 100 percent urbanised, while the rural areas account for more than 40 percent of the population in Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, the Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia, with more than 20 percent in Brunei and Malaysia.

Given all these factors, the question that needs to be asked is, “Why isn’t Southeast Asia making a bigger impact in the food production and supply value chain?” Even worse, food security has become a pressing problem throughout the region.

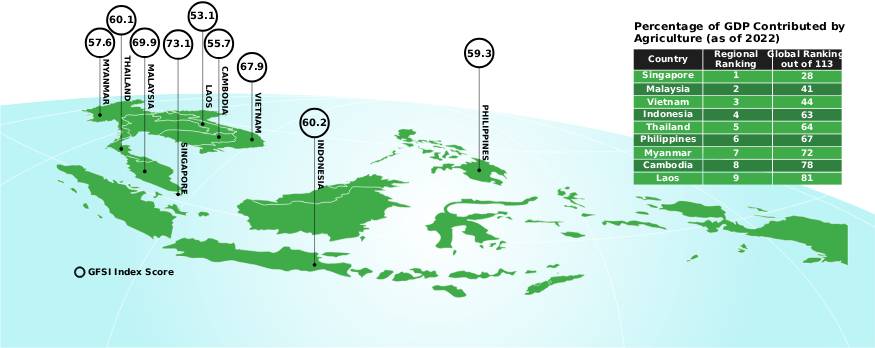

According to The Economist’s Global Food Security Index (GFSI) 2022, which measures the food security situation in 113 economies, only three Southeast Asian countries are ranked in the top 50 percent of the list – Singapore at 28, Malaysia at 41 and Vietnam at 46. The lowest ranked Southeast Asian nation is Laos at 81. There are no metrices for Brunei or Timor-Leste. Ironically, the three countries where agriculture have the highest contribution to GDP – Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia – are the ones with the lowest food security rating.

It should be noted that the GFSI does not only measure the quantity of food, but other factors as well, such as affordability, quality, safety, availability, and how adaptable countries are to supply chain shocks.

Identifying the Issues

So, what is it that plagues food security in Southeast Asia? There is no single answer to that. Instead, the problem can be found throughout the entire food production and supply chain. This means that these have to be tackled individually rather than with one magic bullet which will cure all the woes. The solution to the crisis of malnutrition and food security has to come from a more comprehensive understanding of farming, and has to address the multifaceted layers that comes from producing consumer goods with the respect to nature that has been long overdue in our agricultural industry.

Starting from the upstream, it should be noted that with the exception of cash crops such as oil palm and rice, the vast majority of farms in Southeast Asia are smallholdings of less than 20 hectares. In fact, there are over 100 million farming smallholders in the region who produce 75 percent of food commodities. So, it is a little puzzling that those people who are growing the food are going hungry themselves ,as pointed out by Vandana Shiva, an Indian scholar, environmental activist, food sovereignty advocate, ecofeminist and anti-globalization author. Owing to the small size of their holdings and their limited resources, many of these smallholders face significant challenges, particularly with regards to manpower, costs and yield.

“The monoculture of the mind has succeeded in transforming this country (India) from a land of abundance and pulses and all seeds and cereals and millets, into a land where we are importing fake daals and making fake daals.”

Vandana Shiva, TedXMasala, 2012

To add on to their inhibitions, there are also constraints by the rules and practices of monoculture farming that focuses on a single cash crop, without taking into account the natural relations of the ecosystem, restricted to only using the sanctioned fertilisers under the guise of ensuring quality control.

Another major challenge facing the Southeast Asian agriculture industry is that of post-harvest losses. These are losses to the quantity or quality of agriculture products during the midstream stage – namely handling. storage and transportation. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Report by McKinsey & Company, it reports that “in Southeast Asia, close to 17 percent of total food available is lost or wasted.”

The Possible Solutions

Given the importance of food security to regional integration plans, ASEAN member states have come up with the ASEAN Integrated Food Security (AIFS) Framework, as well as three Strategic Plans of Action on Food Security. As part of the AIFS Framework, seven objectives were identified:

- To sustain and increase food production.

- To reduce post-harvest losses.

- To promote conducive market and trade for agriculture commodities and inputs.

- To ensure food stability and affordability.

- To ensure food safety, quality and nutrition.

- To promote availability and accessibility to agriculture inputs.

- To operationalise regional food emergency relief arrangements.

Inter-governmental agenda aside, technology has been touted one of the key solutions to Southeast Asia’s agricultural issues. These include the use of artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT) and big data for more effective crop monitoring and management, as well as the use of drones to perform tasks such as the spraying of pesticides and herbicides as well as to apply fertilisers.

In Vietnam for instance, cloud-based devices equipped with IoT technology have been rolled-out successfully in the Can Tho province by the government with aid via the Khiet Tham Cooperative and VnSaT project.

Over in Thailand, the Digital Economy Promotion Agency has been giving grants of between US$300 and US$9,000 to farmers for adoption of digital technologies. This has enabled farmers to make use of robotics such as drones, crop seeding robots and harvesters.

Similarly, over in Malaysia, drone companies such as Aerodyne and Poladrone – to name but two – have been providing drones to oil palm farmers to carry out pesticide spraying. In addition, the Malaysian Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC) – in partnership with the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security – has initiated the Digital AgTech programme to help educate farmers on how to utilise digital technologies in their farming techniques.

Even in urbanised Singapore, agritechnology – particularly in the form of urban farms – is being utilised. As part of the country’s 30 by 30 strategy, wherein it aims to produce 30 percent of its nutritional needs, the Singapore Food Agency established the US$44.4 million Agri-Food Cluster Transformation Fund in 2021. The aim of this fund is to encourage urban farming using systems such as aeroponics and hydroponics, which require less land, and can be vertically-integrated into the city-state’s many high-rise public housing units.

Technology has also been put forward as the solution to the problem of post-harvest losses as the use of more efficient machinery and more durable packaging will result in crops being able to better withstand the handling, transportation and storage process.

Interestingly enough, the fertiliser crisis could even be solved through an innovative combination of old-style farming techniques and modern-day R&D.

In the 1970s, Bill Mollison and David Holmgren conceptualised a more a perennial and sustainable form of farming coined as “Permaculture (permanent agriculture)”. They proposed an integrated system of ecological and environmental design that took into consideration all the elements from water source and quality, soil health, companion planting, sunlight, air and living components of both animal livestock. The approach combines the traditional farming methods with the progress of scientific knowledge concerning these issues faced by the farmers to curate a mutually beneficial ecosystem of a food forest, allowing the natural process of decomposition to regenerate the soil alongside its composting method of fertilisations.

To name a few permaculture farms in the region: in Malaysia, the notable name would be Kebun Kebun Bangsar. In Indonesia, there is the valiant work of Kebun Kumara in Jakarta and Bumi Langit in Yogyakarta. Thailand has Sahainan Permaculture Farm in Pai, Thailand. Of course, one could argue permaculture is only feasible for small scale operations and not sufficient for larger, commercial farms.

Given that the population of Southeast Asia is expected to grow by 60 million, it is imperative that the region effectively tackles its food security woes. On paper, it has all the elements needed to help feed the world. But first it needs to adequately feed itself.