In collaboration with Convergence, VOICE OF ASIA is proud to present timeless articles from the archives, reproduced digitally for your reading pleasure. Originally published in Convergence Volume 10 in 2012, we present this story on Chinese New Year, and how it’s celebrated in Malaysia.

For people of Chinese ancestry around the world, the start of the Lunar (or Chinese) New Year is one of the most joyous occasions in the calendar. A time for friends and family to get together, a time to forgive past wrongs and renew friendships, and of course, a time for feasting and merry – making. Chinese New Year has some traditions which are observed no matter in which part of the world those celebrating it may be residing. Join Convergence as we take you through our homeland and show you the joy of this festival through the words of those who celebrate it.

The Prelude to Spring

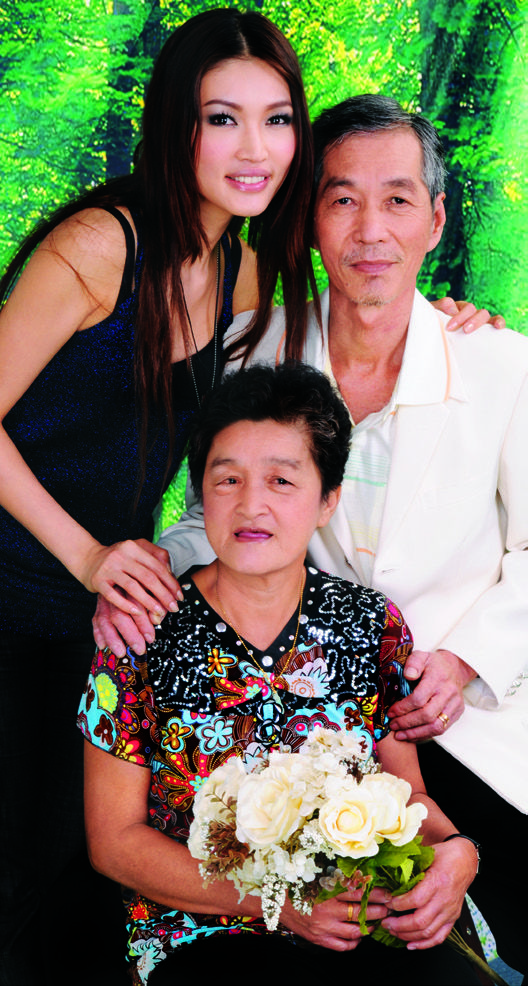

“Chinese New Year is always one of the most meaningful times of the year, and I especially look forward to the reunion dinner which has become even more important as our busy schedules usually prevent us from having a meal together. I want to wish Convergence readers a very Happy and Prosperous Chinese New Year!”

Amber Chia, International Model

For Chinese households, spring cleaning the home is a priority when preparing for the New Year celebrations, as it is commonly believed that cleaning sweeps away the bad luck of the preceding year and prepares the home to receive the good luck of the new. The more enthusiastic homeowners even give their houses a new coat of paint (commonly red), while windows and door frames are decorated with red paper cut-outs of auspicious phrases and couplets in Mandarin characters (chunlian). Sprucing up is not just confined to homes, as another common practice is to buy new clothes and shoes to wear for the new year.

In households which practise Buddhism or ancestor-worship, the house altars and idols are given a thorough cleaning and redecorated. This is also the time when these households also “send off” the Kitchen God with a “bribe” by offering nian gao – a sticky sweet glutinous rice confection. This is to ensure the deity’s co-operation when he reports on the household’s activities for the past year to the Jade Emperor.

While Malaysia doesn’t see the type of mass migration on the scale of China’s annual “chun yun” (spring migration), most of the major highways and arterial roads still see heavy traffic as thousands of Malaysian Chinese and even family members from overseas make the annual trip to return to their home towns for their family’s reunion dinner. Thus during Chinese New Year, some parts of Kuala Lumpur with significant Chinese populations, become virtual ghost towns as most of their inhabitants have left for the festive period.

The Night Before the New Year

Termed “tuan yuan fan” in Mandarin – literally “reunion meal”, this family occasion on the eve of the Lunar New Year sees people from near and far gathering around the dinner table at their family home, or the home of the senior-most member of the extended family. Such importance is placed on this meal that Chinese people living away from their family homes make the special effort to attend this dinner, as heavy emphasis is placed on being reunited with one’s family, especially on the eve. This is, according to the Chinese calendar, the last meal of the old year.

“Chinese New Year is a time of renewal when we look forward to a more hopeful and rewarding time after the trials and tribulations of the previous year. We wish Happy New Year to Convergence readers!”

Dato’ Dr P.H.S Lim and Datin Ho Choy Meng, Malaysian Investors Association (MIA)

Chicken and meats, as well as fish feature heavily in this dinner, as does a particular vegetable called “fat choy” – literally, “hair vegetable” due to its resemblance to human hair. The last plays on the Chinese habit of associating food with equivalent prosperity terms. In Cantonese, fat choy (髮菜) is a near homophone to “fatt choy” (發財) – to strike it rich!

Before the middle of the night when the First Day of the New Year officially begins, many households will also begin arranging makeshift altars outside their house, laid out with food such as glutinous rice, steamed whole chicken, roasted meats, cups of wine, and decorated with paper offerings as well as burning joss sticks. This is to welcome the arrival of the God of Prosperity (財神) who is believed to bring in luck and good fortune to the household for the new year.

A Cultural Occasion

Having dressed up in their New Year clothes, the children then go before their parents and other family elders to wish them health and prosperity, and receive the ubiquitous red packets or “ang pows” from married kinfolk and friends. Households may also engage the services of lion dance troupes to come to their house. The loud noise of the drums and cymbals accompanying the dance is supposed to drive away bad luck and usher in prosperity. Occasionally, the lions will also “peel” a vegetable as part of their performance, due to the homophone association between “vegetable” and “wealth”.

“My wish for the Lunar New Year is that there will be more peace in the world, and more love and understanding, and that everyone will have a fruitful and joyful year ahead. Gong Xi Fa Cai, may your dreams come true!”

Datin Maylene Yong, The Glitterama Ladies Charity Group

The Reunion Dinner

- Poon Choy – translated as ‘Big Bowl Dish’, it is homonymous with ‘Big Bowl of Prosperity’ and features multiple ingredients such as chicken, prawns, abalone, scallops and vegetables layered on top of one another in one huge serving bowl.

- Lap Mei – This is waxed meat such as chicken and duck which were preserved during the winter season and then eaten to celebrate the coming of Spring during the New Year.

- Ba Bao Dai – These meat (sometimes vegetable) dumplings are symbolic of bags of treasure and represent the promise of wealth and prosperity for the New Year.

- Four Treasures – These are hot and cold appetizers to represent the four seasons. Prawns are heavily featured as the Chinese word for prawn – har – represents the sound of laughter and joy.

- Bao – These are steamed buns that are stuffed with a variety of fillings.

- Bachang – Glutinous rice dumplings with fillings such as shrimps, meat, prawns, mushrooms, and salted egg, they are usually served wrapped in lotus leaf or in a wooden steaming basket.

While Chinese New Year is oft perceived as a religious festival, it is not so, as its roots are more cultural than anything. Unfortunately, in Malaysia, many non-Chinese (and some Chinese for that matter) believe that those who do not observe traditional Chinese faiths like Taoism and Buddhism should not celebrate Chinese New Year.

That is not the case, and Muslim Chinese associations in Malaysia have taken pains to keep family bonds strong, the main focus of celebrating the New Year. For example, the Malaysian Chinese Muslim Association (MACMA) has held Chinese New Year celebrations in Kuching, Sarawak for five years running since 2007 in an effort to help Muslim Chinese keep in touch with their culture; with luncheons and family-oriented events and activities to maintain family ties.

“One tradition in our family is to have a lion dance in our house, as a way of ushering in the New Year and to bring greater fortune and prosperity. So for all readers of Convergence, we wish that the lions and dragons will dance in your house, this coming Lunar New Year!”

Dato’ Danny Tan, the National Autism Society of Malaysia, and Datin Rosalind Tan, Yayasan Wanita Cemerlang (below)

Some Chinese Muslim households also go all out to celebrate their cultural roots, with the same reunion dinners and first day traditions such as red packets and new clothes. One notable difference is that all the reunion dishes are halal.

Furthermore, official Chinese New Year celebrations such as the open houses of government leaders are often colourful multi-ethnic affairs, as Malaysians of different races and religions (as well as guests from overseas) come together to celebrate the auspicious occasion.

A Nyonya Flavour

Apart from Chinese Muslims, another offshoot of Malaysian Chinese are the Peranakan Chinese, or Baba-Nyonya, who are found in the old Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca and neighbouring Singapore. Descendants of Chinese traders who intermarried with locals in 103the 15th century onwards, the Peranakan practise several Chinese customs handed down from their forebears, several of which are not practised by other overseas Chinese communities.

Among the Hokkien dialect groups and Peranakan communities in Malacca and Penang, a common sight on the 8th and 9th day of Chinese New Year would be bundles of sugar cane stalks tied together around household altars and community-sponsored public ones, both replete with food and symbolic money offerings. Later on the night of the 9th day, the money offerings and the sugar-cane leaves are burnt as offerings to the Heavenly Jade Emperor.

This festival within a festival originates from Fujian province on the mainland, when the Chinese were fleeing the Mongol invaders seeking to exterminate them. Praying to the Jade Emperor for protection, the refugees hid in a forest of sugar-cane plants and did not emerge until the 9th day of the Lunar New Year when their pursuers had given up.

Hence, for Hokkiens and the Peranakan, the “real” New Year begins on the 9th day, although most will start the celebrations on the 1st day. Interestingly, more and more non-Hokkiens and non-Peranakans are also joining in the 9th day prayers and offerings, as an additional avenue of garnering more prosperity for the incoming year.

Other Peranakan traditions for the Chinese New Year have persisted as well, such as the practice of “soh ja”, whereby the family’s youngsters would kneel in front of their elders on the first day of the new year, wishing them “panjang-panjang umur, banyak banyak untung” (may you have long years of life and many blessings).

“During the New Year, Peranakans will perform sojah where we will be dressed in our best and we kneel in front of our elders and wish them long life and prosperity. I am proud that our culture which combines both Malay and Chinese is so unique, and shows how Chinese New Year is a truly Malaysian occasion.”

Cedric Tan (second from the right), The Peranakan Baba-Nyonya Association of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor

“Chap Goh Meh”, which means the “fifteenth night” in Hokkien, marks the last day of Chinese New Year celebrations with copious last rounds of feasting in most households. The day also featured a major event in the days of yore on the calendars of young single Peranakan youths in the old Straits Settlements. Bedecked in their elaborate kebayas or elegant cheongsams with matching ornaments and jewellery, this would be one of the few occasions the then-tightly guarded Peranakan maidens could go out and parade along the waterfront while being discreetly admired by the opposite sex.

But while social mores in Malaysia have liberalised somewhat, other Chap Goh Meh traditions stay on. The hurling of mandarin oranges into the sea by young single women (and men nowadays) in the hope that their future spouse would pick up the orange continues, and is now a major Chinese New Year event organised by many Malaysian Chinese cultural associations along coastal and urban areas. One tradition which originated in Malaysia, is for women to write their name and contact details on the fruit in the hope that their fated spouse will pick it up.

Come the 23rd of January, the joy of the Lunar New Year will be felt throughout the world as those of Chinese descent will usher in the Year of the Water Dragon. Those travelling to Malaysia during this time will do well not to miss this colourful and momentous occasion. So come join Malaysians from all walks of life and of all creeds and cultures, as we wish you “Gong Xi Fa Cai” – A Prosperous New Year.