In collaboration with High Life: Living the Good Life, VOICE OF ASIA is proud to present timeless articles from the archives, reproduced digitally for your reading pleasure. Originally published in High Life Volume 1 in 2013, we present this story on the Peking Opera, an art with a long, storied history etched in Chinese tradition.

An explosive showcase of Chinese heritage, the Peking Opera is a spectacle of vocal melodies, mesmeric acrobatics, entertaining mime, marvellous music and fascinating costume. The theatrics weave a story of Chinese culture through vivid colours and performance, as an orchestra provides a gripping accompaniment to the drama. HIGH Life peeks behind the curtain of this wonderful 200 year-old tradition.

National Treasure

An intangible treasure of China, the Peking Opera dates back to the late 18th century and achieved prominence in the Qing Dynasty court. Developing in size and popularity over time, the performance became more accessible to the public, and now takes pride of place annually in the Peking Opera Theatre. The largest and most extensive Opera of its kind in China, the quality, number of artists and influence are incomparable. The repertoire includes over 1,400 different works that cover a range of topics, with inspiration drawn from traditional stories, historical novels and political and military conflicts throughout China’s history.

Little emphasis is put on historical accuracy as the focus is upon artistic content, with the ultimate ambition for the performers being beauty in every single motion. During training performers are severely criticised if they lack finesse in their movements, and reaching the level of mastery on-show at the Opera takes many years, with the arduous learning process beginning at a very young age. Initially trained in acrobatics, performers then learn singing and artistic gestures.

Colour and Creativity

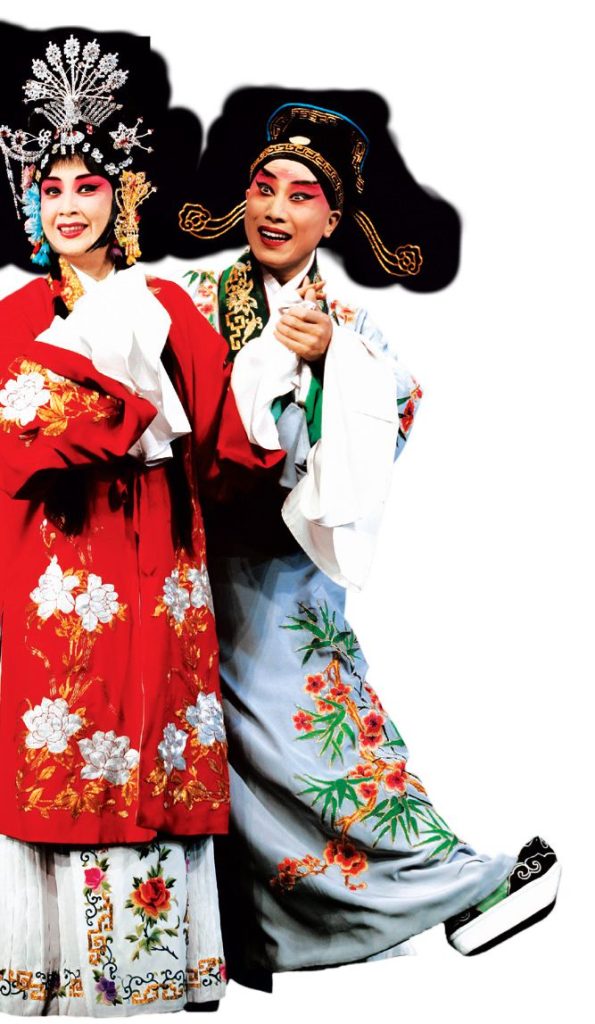

The performance is a blitz of colour and sound, but once an audience member understands the classifications and nuances of the performers, he is ready to enjoy the drama. The opera is a blend of peaceful scenes and battle enactments delivered through music, verse recitation, prose dialogue, and non-verbal vocalisation, with the intensity or softness indicating which. Audiences can also distinguish a character’s gender and status at first glance by the type of headdress, robes, shoes and baldrics associated with the role.

Four distinct outfits underpin the major characters. Male roles are divided into Lao Sheng, an old man either a distinguished official or scholar, Xiao Sheng depicting a young man or warrior in elaborate dress, and Wu Sheng, a man of great physical skill, like an acrobat. The female role has similar divisions, with an elegant woman entitled Qing Yi, a flirtatious female in Hua Dan, a young unwedded girl Gui Men Dan and Dao Ma Dan, a female warrior. Wu Dan is a female acrobat and Lao Dan depicts an old woman. The cast is completed by the forceful Jing, a man with a painted face often playing the part of a high-ranking military man, and Chou, the amusing scoundrel or jester.

Masked Magic

There is plenty happening at the Opera that is not being said. The message communicated through the costumes, face paint and masks speaks just as loudly as the lyrics behind the harmonies, and much weight is attributed to gestures, settings and the art form. With a minimal amount of props, the Opera relies upon symbolism to assist the story. The straightening of a costume is a sign that an important character is about to speak, and walking in a large circle symbolises travelling a great distance. When actors master the complicated art of changing ‘moods’ it is also spectacular. Performers rely on four ways to inform the crowd that their feelings have changed.

A mask that has been hidden on the actor’s head can be pulled down over the face, and its colour will depict the mood – blue for anger, black for sadness, and red for happiness. A second method is changing the colour of a beard, from black to grey or white to express emotions of anger or excitement. Thirdly the actor can blow dust concealed in the palm, back into the actor’s face. Lastly the actor can draw out greasepaint concealed in eyebrows or sideburns to mirror a fluctuation in mood. Skilled artists have dedicated a lifetime to perfecting the art, ensuring that the Opera’s traditions and performance will intrigue and enthral audiences for generations to come.

The Peking Opera house of Beijing has been invited to perform in many countries from the United States to Germany, Australia to Japan, and Brazil to South Korea and in doing so has strengthened relations between China and these nations. From a collection of troupes in 1790 that performed on stages dimly lit by oil lamps, the Opera has become a cultural and entertainment phenomenon – preserving valued traditions through the energy and expertise of a new generation.