In collaboration with High Life: Living the Good Life, VOICE OF ASIA is proud to present timeless articles from the archives, reproduced digitally for your reading pleasure. Originally published in HIGH Life Volume 1 in 2013, we present this story on snakes, in celebration of the year of the snake, looking at what these slithery beings have meant to humans throughout the ages.

This Chinese New Year belongs to the mighty snake. A fascinating animal, the serpent conjures different, colourful imagery across the globe. Ancient myth, religious fable, medicinal power and cultural reverence have all contributed and competed to polarise how entire populations view the fearful beauty of this legless marvel that can both mesmerise and kill. The scales of favour for the snake have tipped both ways throughout time, creating generations of admirers who revere its majesty, and spawning a generation of ophidiophobics, scared of its power and venom. In celebration of the coming year of the Water Snake, HIGH Life explores the winding path the serpent has taken through history.

China Power

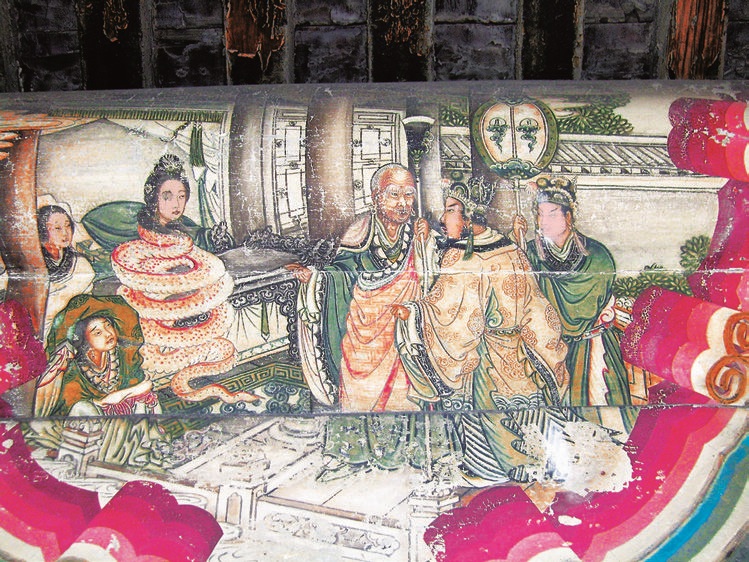

The year of the Snake brings with it a fresh opportunity, and just as the snake sheds its skin, there is a chance for a new beginning, a shedding of the shadows of the previous year. It is, therefore, appropriate that we begin the tale of the snake’s fortunes with its journey through Chinese history. Here, the snake sheds its negative connotations and is thought of as a cultural symbol of discretion, wisdom, flexibility and beauty. The presence of the reptile is considered a good omen, the embodiment of intelligence and wisdom.

Intelligent though it may be, this does not render it untouchable. Chinese traditional medicine does not hesitate to use the powerful qualities that the snake possesses for healing purposes. There are at least three features that capture the attention of traditional healers; snakes have an incredible flexibility and speed, they shed their skin, and some are poisonous. The flexibility is thought to be a vital quality in which to combat joint stiffness, for example arthritis. The shedded skin is used to aid the regeneration of human skin, with ailments reportedly cleared up with the application of snakeskin to the affected area. When the neurotoxins of snake poison are administered orally in controlled doses, they have a positive impact on the nerves and remedy the over-contraction of muscles.

The snake is the sixth in the 12-year cycle of the Chinese New Year, and Ancient Chinese wisdom says a snake in the house is a good omen because it means your family will not starve. Giving the snake yet more power in the East is its association with religious deities. From here, the story moves to India.

Indian Enchantment

In India, the snake is a source of wonder. When coaxed out of a cane basket with pipe music and made to sway hypnotically, the snake draws a crowd, and in special celebrations in the calendar it can look forward to being revered, fed treats and treated handsomely in this South Asian nation. The snakes’ plaudits soar to even greater heights within Hindu mythology – to the level occupied by the Gods. In the religion of Hinduism, Shiva the Destroyer wore a garland of snakes to symbolise wisdom and eternity, as it is perceived that the shedding of its skin gives the serpent a seemingly everlasting life cycle.

The second god in the Hindu triumvirate, Vishnu did not arrive merely wearing a snake; he rode upon one. His serpent Ananta, also known as Shesha, again embodies the vision of immortality and infinity, being the avatar of the Supreme God. Shesha is said to hold all the planets of the universe on his hoods and it is said that when Shesha uncoils, time moves forward and creation takes place. When he coils back to his original position, the universe ceases to exist.

The religious festival of Nag Panchami involves a ritual based on the tale from Hindu scripture. According to lore, it is believed that the Kathmandu valley of Nepal used to be a vast lake. When humans started to drain the lake to make space for settlements, the divine, serpent-like Nagas became enraged. To protect themselves against the wrath of the Nagas, humans gave them areas as pilgrimage destinations, restoring ‘a harmony within nature’. While the humans were safeguarding themselves against the Nagas, Buddha used the seven-headed serpent to protect as a more than able bodyguard. But while snakes protect Indian Gods when they are alive, another nation, Egypt, saw them as guardians of the afterlife.

Pyramidal Pythons

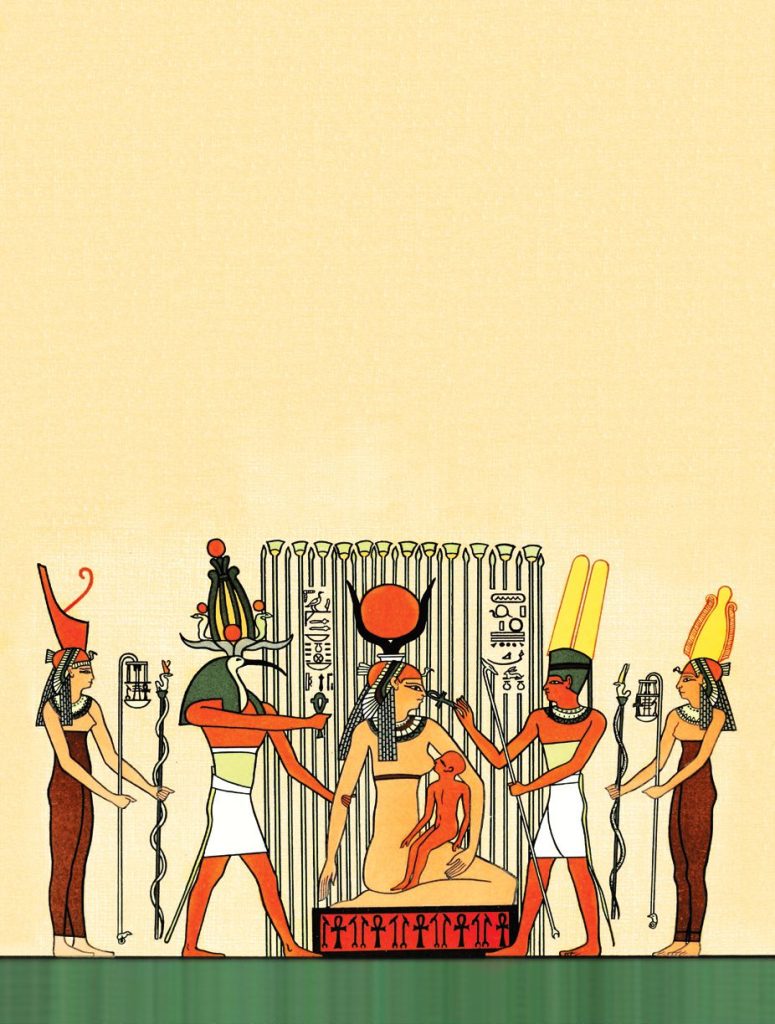

Just as the river Nile winds its way through Egypt, so too the snake is laced through ancient Egyptian history which records a complicated love/hate relationship with the reptile. They were viewed as a protector of the King, yet also portrayed as demons of the underworld. Either way, Egyptian history shows the homage paid to the snake, with headdresses and outfits laced with snake-shaped detail, mummified serpents immortalised in tombs and wonderful tales inspired by the hieroglyphics that depict the slithering creature twined around the neck of the Gods.

The snake also makes an appearance in their alphabet. Pre-attack, the feared Horned Viper flexes its coils together as it explodes forward, with a sound that mimics the letter ‘f’; therefore the horned viper became the hieroglyphic symbol for the letter. Incidentally ‘fy’ is the Egyptian word for ‘viper’. Snakes occur in the tomb-texts frequently, not as animals but as Gods.

The snake God Apophis was the ancient Egyptian spirit of darkness and destruction and threatened to destroy the sun God Ra when he travelled through the underworld. It was tasked to the serpent-headed male deity Mehen, who protected the sun, to cut a hole in the belly of Apophis to release Ra from his clutches. The Delta area of Egpyt was ruled by the cobra goddess Renenutet, whose powerful gaze was able to destroy enemies. Ancient Egyptians felt no need to fear her however, as she provided them powerful protection in their lives. With the epithet ‘She Who Rears’, Renenutet gave each baby a secret name along with its mother’s milk and protected children from curses. A child was said to “have Renenutet upon his shoulder from his first day.

When her lover Mark Antony took his life after losing the battle of Actium, his soul mate – the beautiful Cleopatra – followed suit, her history suggesting that the venomous bite of an Asp caused her deliberate death. In reality it was more likely to be the King Cobra, as the Asp is not a native snake of Egypt. Its flared hood and deep, dog-like growl makes the snake – which can raise a third of its body length to stare its prey in the eye – a truly horrifying sight that makes the blood run cold. However, when delving into Greek mythology, we discover that the Cobra is not the only snake-related horror to frighten those in its path.

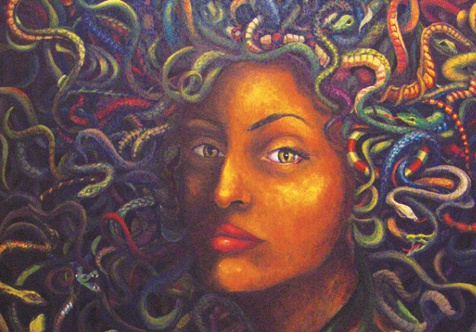

Medusa and Medicine

We have all suffered that famed ‘bad hair day’ but just one look at the locks of Greek protectress Medusa would have been your last. With venomous snakes in place of hair, a single glance at the serpents on her head would turn the witness into stone. Once a beautiful woman, the myth says that Medusa asked the Goddess Athena if she could see the sun. When her request was turned down, Medusa recoiled and accused Athena of being jealous of her beauty. In response to that accusation Athena raged, and replaced Medusa’s hair with writhing snakes that hissed and fought each other atop her head, ensuring that a loving gaze or passing glance would never be made in her direction again.

In total contrast to their use as a vehicle for visual repulsion, the varying fortunes of the snake are encapsulated within the very same country in a conflicting viewpoint – using the serpent as a sign of good, not evil. The God of medicine and healing Asclepius carried a serpent-entwined staff. The symbolism of this has been interpreted in different ways, among which the fact that snake products were used to treat patients in ancient times. The serpent also represents the forces of life and death, just as a physician stands between healing and destruction or perhaps alluding to how the snake’s ability to shed its skin represents a triumph over ageing.

The famous healing temples of Asclepius located at Epidaurus and Trikala allowed a particular type of non-venomous snake to be used in healing rituals in honour of Asclepius. These Aesculapian Snakes slithered around freely on the floor in dormitories where the sick and injured slept, and so influential was the cult of Asclepius that from 300 BC onwards, pilgrims flocked to his healing temple to be cured of their ills. The staff itself, serpent entwined, is a worldwide symbol of medicine to this very day.

Nordic Mythology

Certain snakes are synonymous with encircling and squeezing the final gasping breath out of their prey. In the Nordic mythological story of Jörmungandr however, the serpent grew so large after being cast into the sea that she was able to grip the entire Earth in its tail, constricting the planet and upon her release, ending the world. The sea serpent – the middle child of Angrboða and the god Loki – was tossed into the ocean and famously became an adversary of the Norse God of thunder, Thor.

In Thor’s youth, on a fishing trip with a giant called Hyamir, he encountered Jörmungandr, who advised Thor to stop rowing when they had reached his regular fishing spot. Thor ignored the advice, and rowing his boat to the edge of the world, dropped his line; whereupon he encountered the mighty sea-snake who took his bait. A furious battle of strength ensued but just as Thor raised his hammer to finish off the beast, Hyamir cut the line, enraging Thor and sending the serpent to the depths where it avoids the Norse God – but not forever. It is said that Thor is destined to exact revenge on the Midgard Serpent on Ragnarok the end of the world, when earth and the underworld is destroyed, the oceans leave their beds, the heavens are torn apart and creation and time itself is shattered, causing a great battle between the Gods and evil and providing Thor a chance to crush the skull of his old foe once and for all…

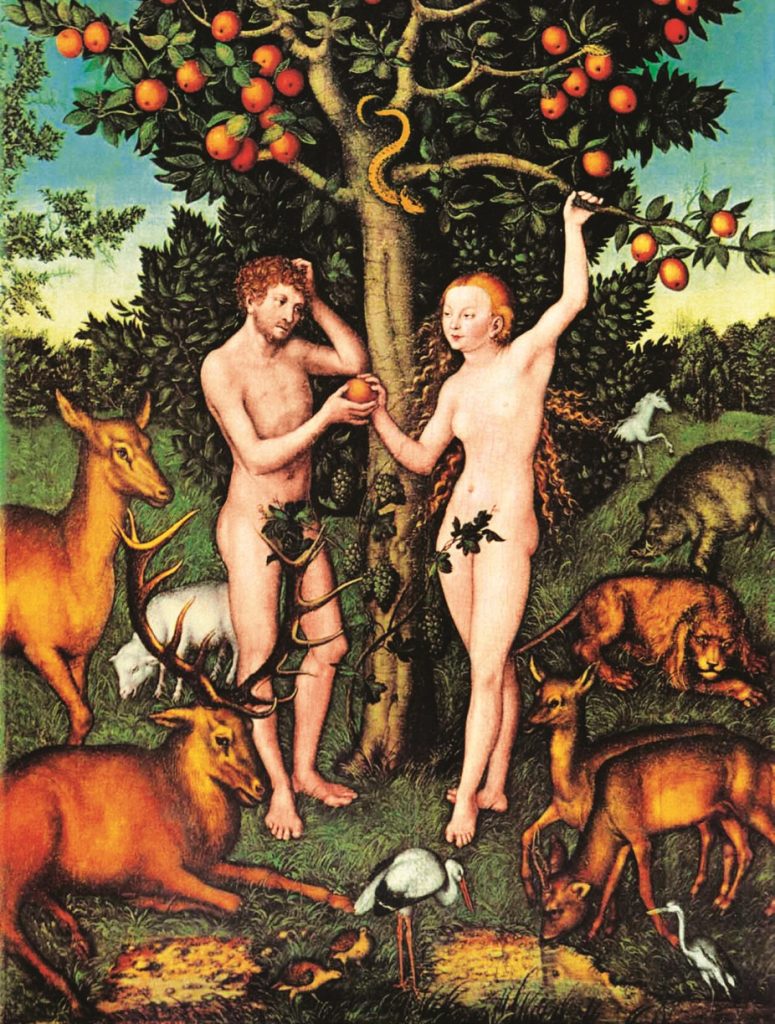

The Snake of the Bible

If the story of the Bible is to be believed then the snake did not play a mere bit part in the history of man but is the protagonist for the existence of evil and sin in the world – no mean feat for this usually retiring reptile. Demonised in the holy book of Christianity, the snake is reviled as a ‘serpent’ who spoke to Eve, and with charming words tempted her into taking a bite from an apple, plucked from the forbidden tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden. The serpent beguiled Adam’s innocent mate with the promise of power greater than God himself – if only she would sink her teeth into the delicious fruit.

Prior to the snakes’ interference in proceedings, Man and Woman were not ashamed of their nudity, had no urge to give in to sweet temptation or even a thought of defying the word of God and eat – until, of course, they were seduced by the fork-tongued fiend. The tale is an oft-repeated parable in the lesson of self-control and rule-breaking. In the myth, God doled out punishment not only to mankind but to the snake, commanding ‘upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life’ as an eternal ‘punishment’ for the reptile’s insubordination.

Artistic interpretations of the scene have been depicted for centuries, cementing the image of the snake as cunning and shifty. In etymological terms this is certainly where the negative connotation of branding a sneaky, conniving, person a ‘snake’ – due to their untrustworthy personality traits – originates from. However, not everywhere in the world is the snake at odds with those thought to rule the heavens.

Aztec Wonder

For the South American Aztecs, the snake was not the enemy of god, leading man into temptation. The snake was god. The deity Quetzalcoatl – whose name is derived from the Nahuatl language and translates as “feathered serpent” – was recorded as being worshipped from as early as 400BC.

The iconography of the god is prominent in Aztec temples and decoration in the ancient city of Teotihuacán in Mexico, his image bringing together the magnificent green-plumed quetzal bird to symbolise the heavens and the wind, and the snake, symbolising the earth and fertility.

In the Aztec creation myth, Quetzalcoatl’s cosmic conflicts with the volcanic-glass-adorned Jaguar-God Tezcatlipoca, brought about the creation and destruction of a series of four suns and earths through flood and fire, leading to the fifth sun and today’s earth. At first there were no people under the fifth sun that he created. The inhabitants of the earlier worlds were wiped out, and their bones littered the underworld.

Quetzalcoatl and his twin journeyed there to find the bones, infuriating the Death Lord whose duty it was to guard the deceased for all eternity. While fleeing from the underworld and defying the laws of the dead, Quetzalcoatl dropped the bones he was carrying and they shattered into a million pieces. So he gathered the pieces and took them to the Snake Woman earth-goddess Cihuacoatl, who ground them into fine flour. They moistened the flour with his own blood, giving it life and cementing his legacy – and the reputation of snakes – as the most sacred and respected of life on earth. While the Aztec God is credited with creating the sky, further north there is a belief that the snake merely occupies the clouds above.

Cherokee Coils

The ‘great snake’ plays a prominent role in the mythology of the Cherokee, as they hold the belief that the sky is a winding serpent, wrapping its body and tail around the stars, like a rattlesnake, winding itself back and forth in a side-winding motion across the milky way.

The American Indians had many stories of snakes. The rattlesnake in particular was considered the ‘leader’ of all snakes, and a tribesman should not take the life of this creature and if killing was unavoidable, he should atone to the snake ghost. Failure to do so would evoke the vengeance of the Black Snake, who would hunt down a member of the ‘murderer’s’ family and sink its fangs into the him or her, causing a painful death. Such tales made the creature highly revered and much respected.

The horned serpent of Uktena appears in many North American tales, as wide as a tree-trunk with horns upon its head and scales like glittering sparks of fire with a blazing, diamond-like crest upon its forehead. So dazzling is the ‘diamond’, many tribesmen tried to ‘win’ it, dazed by the bright light and running towards the serpent instead of escaping from it. The 52 years of the Cherokee calendar are reflected in the number of scales on a rattlesnakes mouth. From North America, across the continents to China, there can be no greater accolade for the snake to have achieved – a prominent role in the dating-system, in the calendar of civilisation.

It is thought that a person born in the Chinese year of the snake is intellectual, superstitious, sceptical, astute, and has elegance, innate wisdom, and possibly some level of supernatural capability. Whether or not this is true of the individual, it can certainly be applied to the snake itself throughout history. Miscast in some quarters and heralded in others, the fact that entire civilisations revolved around the perceived wonder of this reptile is astounding. It shaped the gods of Egypt, the course of medicine and the fabric of romance. In 2013, all eyes will be on the snake, but it has had plenty of practice in the spotlight, having captured our attention and spellbound humankind for thousands of years.