In collaboration with HIGH Life: Living the Good Life, VOICE OF ASIA is proud to present timeless articles from the archives, reproduced digitally for your reading pleasure. Originally published in HIGH Life in 2014, we present this story on Yap Ah Loy and the monumental legacy he left behind – Kuala Lumpur.

Throughout history, Malaysia has enjoyed a unique and mutually beneficial relationship with China, one of the world’s oldest and most established civilisations. HIGH Life explores some of the most important milestones in this relationship which has shaped both nations. In this issue, we look at the life and achievements of Yap Ah Loy – the man who laid the foundations of modern Kuala Lumpur.

The political, economic and cultural capital of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur (also affectionately known as KL) is a bustling conurbation where approximately 6 million people live and work, and millions more – from near and far – visit each day. It is the pulsating heart of the nation, an alpha world city which places it at par with other municipalities such as Beijing, Madrid and Los Angeles.

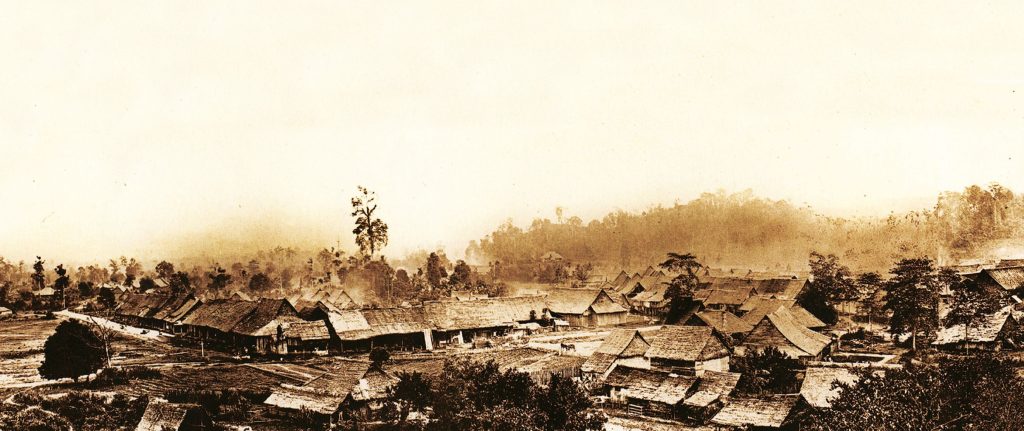

150 years ago however, KL was a far cry from being the powerhouse that it is today. Instead it was a small settlement founded by Chinese labourers who manned the tin mines in the area. It was a ‘Wild West’ sort of town – prone to the occasional flooding, with little infrastructure to speak of, and ridden with internecine gang wars. One man – Yap Ah Loy – took up the challenge of revamping Kuala Lumpur and in doing so set the ball rolling for it to eventually become ‘The City That Never Sleeps’.

It is said that the Chinese character for “crisis” is made up of the one for “danger” and “opportunity”, and the unspoken rule is that those who have the nous to do so are able to maximise the benefits from any quandary.

Yap Ah Loy can be said to have been such a person. Born on the 14th of March 1837 in a small village in the Fui Chiu prefecture of Guangdong province, he was brought up in a China on the decline. Western powers were encroaching on Chinese territory and just five years after his birth, his homeland suffered the indignity of losing the First Opium War, leading to the first of what would become many ‘Unequal Treaties’.

Compounding the issue was the corruption, feudalism and poor government of the Qing Dynasty. Poverty was rife and opportunities were few. It was during this time that many young Chinese men decided to risk life and limb by embarking on a long and perilous journey across the South China Sea to Nanyang (southern ocean – the Chinese metaphor for Southeast Asia).

They were told that there was employment there, particularly in the tin mines located in British-ruled Malaya. The trip was long and uncomfortable, the work hard and back-breaking but it was a chance to escape the grim future that they faced in China. In 1854, a 17-year old Yap Ah Loy became one of them, joining contractors when they came to his village to look for labourers to work in the tin mines of Malacca.

He never looked back.

Seizing Opportunities

Shortly after arriving in Malacca, Yap went to work at the tin quarry in Durian Tunggal. However, the tin trade there was not doing particularly well and the young man knew that staying on would be futile. After four months, he left and made his way to Kesang in Muar, Johor where he would find employment as a shop assistant for a relative.

One year later however, it looked as though Yap Ah Loy’s Malayan adventure was at an end, as poor business meant that the said relative was unable to keep him on the payroll. Rather than let his kinsman flounder in a strange land, Yap Ng (for that was his name) gave Ah Loy the equivalent of a hundred dollars to sail to Singapore and take a ship back to China from there.

The first part of his journey home, which was getting to Singapore, went off without a hitch. The second, however, did not work out quite as planned. A stroke of ill-fortune resulted in Yap losing his money, leaving him unable to pay for his ticket. Unable or rather unwilling to ask for help, Yap Ah Loy was stranded.

As some have said, “Adversity introduces a man to himself”, and just as the old adage about “crisis”, “danger” and “opportunity” goes, Yap decided to make the best out of a bad situation and seek his fortune in Malaya. He went north to the town of Lukut in Negeri Sembilan.

Back on Track

In Lukut, he worked as a cook and handyman until he had saved enough money to start a small business selling pigs in return for tin, which he would then trade with tin merchants.

His business flourished and Yap expanded operations to Sungai Ujong and Rasah, where he made friends with Liu Ngim Kong, a fellow clansmen and commander of Sungai Ujong’s Kapitan Cina (Chinese Captain).

In 1861, Liu went to KL to become the head commander under Hiew Siew, the first Kapitan Cina of KL. Within a year, Hiew had died and Liu assumed the Kapitancy, inviting Yap Ah Loy, who became one of his most trusted lieutenants, to help manage his business. Recognising the town’s great potential – long before it became a main source of tin for the British Empire – Yap quickly accepted the offer.

Just six years later Liu Ngim Kong died, leaving the Kapitancy to Yap Ah Loy in his will. A brief tussle for power ensued among the Chinese elite, but a ruling Malay chief revealed that Liu’s last wishes were approved by the Sultan. In the following months, Yap would begin to realise his full potential, establishing a capable administration and a strong fighting force to cope with mounting tensions between rival Malay chiefs around KL.

By 1870, the Selangor Civil War had erupted into open fighting, and Chinese and Malay factions on both sides advanced on KL. In August 1872, the town fell to a Malay warlord named Syed Mashhor. But Yap Ah Loy quickly recovered, assembling a force of nearly 2,000 in two months. He led his men personally and encircled the enemy, forcing them out after two days and nights of fighting.

Man in Charge

In the ensuing period of peace, Yap Ah Loy resumed his work as administrator of KL and led the recovery of the town’s mining industry. He also revolutionised its infrastructure, transport facilities and public and emergency services, establishing KL as an economic centre and resulting in it being chosen as the state capital of Selangor in 1880.

In the wake of fires and floods in 1881, the town – which had predominantly consisted of wood and atap structures – was almost entirely destroyed. In response, the British Resident of Selangor, Frank Swettenham ruled that all new buildings had to be constructed of brick and tile. Again, Yap Ah Loy saw an opportunity and seized it. He purchased land to set up a brick-making plant which soon powered the redevelopment of KL. The area where his factory stood is known today as Brickfields.

Birth of a City

With his visionary planning and political influence, Yap Ah Loy restructured the burgeoning city’s layout using architectural styles reminiscent of those found in China, characterised by ‘five foot ways’. This would become another element embedded in Malaysian culture, as reflected by the Malay expression kaki lima (literally, five foot) to describe most types of walkways.

Yap Ah Loy was also instrumental in the establishment of a railway line, a Sanitary Board and arterial roads like Ampang Road, Pudu Road and Petaling Street which linked the city to nearby tin mines. He also instituted strict measures to curb crime, parading thieves on the streets with the stolen item tied to their shoulders. Repeat offenders would have their ears cut off and those who broke the law a third time were impaled through their throats as they knelt. While draconian, these measures were an effective deterrent against crime and Yap was able to maintain order in the mining town of over 10,000 inhabitants, with only a token police force of six officers.

Perhaps the greatest recognition of Yap Ah Loy’s efforts came after his death in 1885. KL was chosen as the capital of the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1896, thanks to its capable infrastructure and numerous strategic advantages such as being in the centre of the four states in the FMS (Selangor, Pahang, Perak and Negeri Sembilan) and access to shipping lanes through the Klang River.

Above all, the city benefited from a solid economic foundation and advanced infrastructure. Both of these were legacies of Yap’s administration, making KL a very conducive place to do business. Furthermore, in the following years, consistent development maintained the city’s prominence.

Throughout the various incarnations of the country – from British Malaya to the independent Federation of Malaya and finally to the current day Federation of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur has held prime position as the national capital. Today, the Father of Modern Kuala Lumpur is remembered through Jalan Yap Ah Loy (Yap Ah Loy Road) – a major thoroughfare in the city he helped create. However, perhaps the bigger tribute to Yap Ah Loy is Kuala Lumpur’s continuous importance in the socio-economic and political fabric of Malaysia and its position as one of the great cities of Asia. It is a city that is one of the most prosperous Southeast Asian economic centres thanks to its first-class infrastructure and public services – traits that can be traced back to Yap Ah Loy, a man who dared to dream and instigate change.